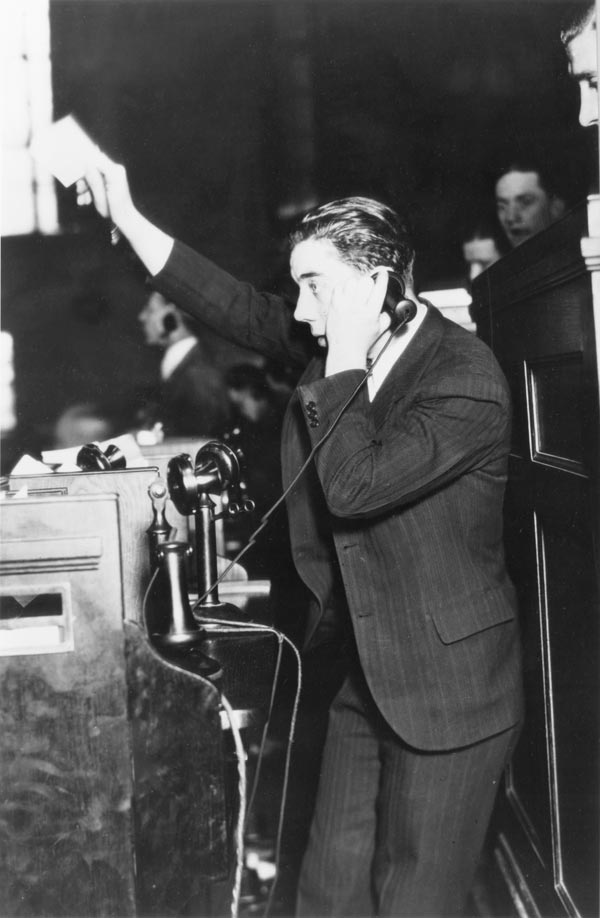

Through the Great Depression, the majority of stock transactions were for individual accounts. “Mom and pop” investors who bought small quantities of shares were not likely to worry about commission costs, and some wealthy individuals who bought large numbers could do so for no cost at all from their seats on the exchange. But, after World War II, things changed quickly as institutional investors—mutual funds, pension funds, insurance companies and the like—became more prominent in the American economy. From 1946 to 1952, institutional investors bought two-fifths of all new issues. And by 1958, one quarter of all purchases and sales of stocks were by institutions.

Since commission rates were fixed, institutional investors were understandably resentful of the NYSE monopoly over listed stocks. Because NYSE members could trade listed stocks on the regional exchanges, institutional investors began seeking membership on these markets. The first was Waddell & Reed, a mutual fund that joined the Pacific Coast Stock Exchange in 1965. While the regionals welcomed such business, the NYSE did what it could to stop it. By the 1960s the rise of institutional investors had even created what was sometimes called a “fourth market” in which “upstairs” broker-dealers representing institutions could negotiate the commission rates on block trades of 10,000 shares or more upstairs and then “cross” them (matching buyer and seller without posting the trade on the exchange) on the floor. The NYSE also provided a loophole in the fixed commission system by sanctioning “give-ups,” which involved returning a portion of the commission rate to the seller in return for nominal extra services.

In the late 1960s the SEC subjected the market distortions created by fixed commission rates to sharp scrutiny in its investigational hearings on rate structure of the national securities exchanges. Its next step, at the behest of Congress, was to conduct a comprehensive analysis of changes in marketplace due to the rise of institutional investing. On March 10, 1971, the SEC released its Institutional Investor Study Report , “an economic study of institutional investors and their effects on the securities markets, the interests of the issuers of securities, and the public interest.” The study clearly indicated that the specialist system was under stress and raising concerns. Specialists were not handling block trades, and many were not even carrying out their market making responsibilities which, under the terms of the 1934 Exchange Act, included a responsibility to maintain liquid markets by selling when demand was high and buying when demand was low. Instead, the study found, those who carried out their market making responsibilities earned less than their less conscientious counterparts. The study declared that the objective should now be to create a “strong central market system” open to brokers and institutions, motivated by competition, and governed by regulation. 3

The NYSE hoped that, after a stint as Federal Reserve Chairman, its former president would have sufficient standing to draw up a friendly, yet effective counterproposal. William McChesney Martin’s report, commissioned by the NYSE and published in August 1971, ruled out institutional membership and competition between market makers. Martin’s solution was to combine all of the specialist markets into a single auction market and to bar the OTC market from handling listed stocks altogether. “The New York Stock Exchange has, to some extent, all of the characteristics prescribed above for the proposed national exchange system,” Martin concluded. 4 No one besides the members of the exchange were convinced, for other events had discredited “business as usual” on Wall Street.

The Martin report blamed the issues in of the securities markets on “the appearance of two new forces: institutional investors and computers.” 5 In truth, the largest disruption was caused more by lack of automation, for while corporate America was steadily computerizing in the 1960s, broker-dealers, shielded from competitive pressures by fixed commission rates, did not, leaving them woefully unprepared for growth. In 1964, the average daily volume on the NYSE was $4.89 million—four years later, it hit $14.9 million. A “paperwork crisis” began in 1967. Throughout the financial district stock certificates were piling up, even as clerks worked seven-day weeks and brokerage firms hired third shifts. Although the NYSE intervened to help its members (some of whom were now computerizing as quickly as possible), the pressure was too great—the first firm to fail was Pickard & Company, in May 1968.

The paperwork crisis was followed by financial turmoil as the nation entered the recessionary 1970s. In the year after May 1969, the Dow Jones Industrial Average dropped 35 percent. This market shock resulted in the disappearance of 160 NYSE member organizations, about half of them to merger. As brokerages failed, the NYSE helped cover investor losses out of a trust fund. The October 1970 closure of Goodbody and Company, the nation’s fifth largest brokerage, cost $21 million. An unfortunate side effect of the paperwork crisis was that it enabled dishonest market participants to appropriate funds undetected. By one estimate, some $100 to $400 million was stolen from investors between 1964 and 1969. 6 Investors protested and Congress listened. In December 1970, Congress passed the Securities Investor Protection Act, creating an insurance fund providing up to $50,000 to investors with SEC registered broker-dealers.

Having created this fund, Congress then took steps to ensure that the likelihood of losses would be minimized. It gave the SEC more sweeping regulatory powers—enabling it to demand that the exchanges step up examinations and require more detailed financial reporting from its members. But legislators also began to suspect that the problem was more than just a matter of policing—it was systemic. Broker-dealers were relentlessly entrepreneurial—through the 1960s, they had focused on selling, giving insufficient priority to the necessity to manage all that new business effectively.

(3) Joel Seligman, The Transformation of Wall Street: A History of the Securities and Exchange Commission and Modern Corporate Finance, 3rd (New York, 2003), 497.

(4) The Securities Markets - A Report, with Recommendations, by William McChesney Martin, Jr., August 5, 1971, 5.

(5) The Securities Markets - A Report, with Recommendations, by William McChesney Martin, Jr., August 5, 1971, 2.

(6) Seligman, The Transformation of Wall Street, 457.

(Courtesy of Kathryn McGrath)